PID Control

The math core of precise motion—ensuring your AGVs hug lines, ace corners, and hold speed steady, load or terrain be damned.

Core Concepts

Setpoint (SP)

The goalpost your robot chases, like a target speed, map coordinate, or the heart of a magnetic tape.

Process Variable (PV)

Real-time data straight from the sensors – it's where the robot actually is right now, compared to where it wants to be.

The Error (e)

Calculated non-stop as . The PID controller's one job is to wipe out this error as fast and smoothly as possible.

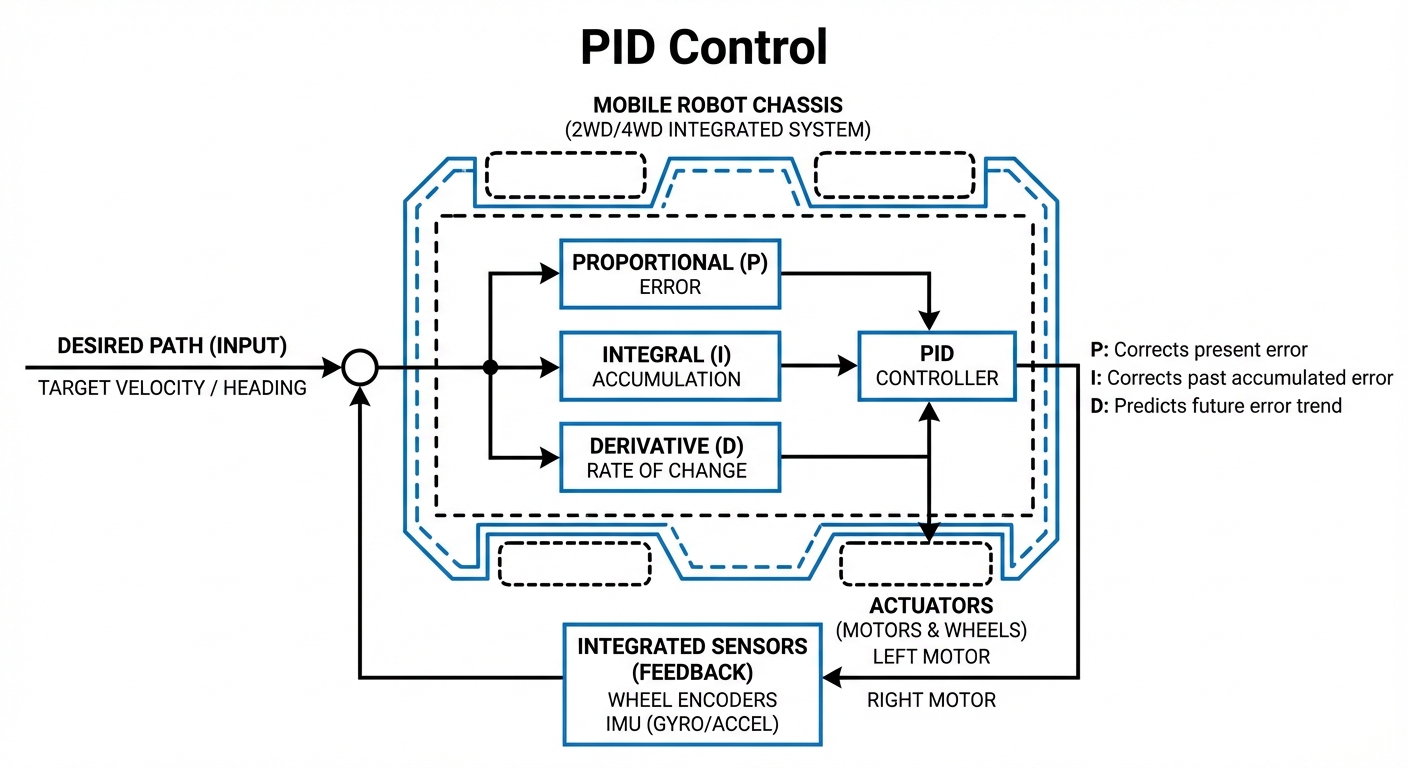

Proportional (P)

The instant response. It spits out an output that's directly proportional to the current error. Big errors trigger big corrections, but it often leaves a lingering steady-state offset.

Integral (I)

Looks back at history. It adds up past errors over time to wipe out the steady-state offset that Proportional alone can't handle.

Derivative (D)

Thinks ahead. It checks the error's rate of change to cut down overshoot, stop wobbling, and keep everything stable.

How It Works

For an Automated Guided Vehicle (AGV), PID is like the central nervous system for movement. Picture an AGV tracking a line on a factory floor – sensors are always spotting where that line is compared to the robot's center.

If it veers left, the error spikes. The term kicks in with a right turn. But basic controllers might blast past the line. That's where the term steps up – it detects the sharp direction change and hits the brakes on the turn for a smoother landing. Meanwhile, the term makes sure constant drags (like a sloped floor) get just the right extra motor power to stay dead center.

This loop fires off hundreds or thousands of times a second (that's Hertz), blending P, I, and D outputs to nail the perfect voltage or PWM signal for the motors.

Real-World Applications

Precision Line Following

Keeps AGVs glued to magnetic tape or painted lines in cramped warehouse aisles, even at top speeds with barely any wandering.

Adaptive Speed Control

Holds steady speed as an AGV climbs from flat ground onto a ramp, fighting gravity and varying loads.

Robotic Arm Positioning

Powers mobile manipulators so the arm nails the exact pick/drop spot without shaking or overshooting.

Dynamic Obstacle Avoidance

Smooths out path changes when an AMR (Autonomous Mobile Robot) dodges a person or obstacle on the fly.

Frequently Asked Questions

What distinguishes PID control from simple On/Off control?

Basic on/off control means jerky starts, stops, and wobbling around the target – that's 'hunting.' PID delivers smooth, error-scaled output for gentle slowdowns near the goal and rock-solid holding.

Why does my AGV wobble or 'wag' its tail while line-following?

Usually too much Proportional ($K_p$) punch or not enough Derivative ($K_d$) to calm it down. The robot overreacts to tiny errors, blasts past the line, then swings back hard – hello, wavy pattern.

How does payload weight affect PID tuning?

Hugely. A loaded robot has way more inertia, so it needs totally different PID gains to speed up and brake right versus empty. Smart AGVs use 'Gain Scheduling' to swap settings on the fly based on load weight.

What’s 'Integral Windup' and why does it wreck motors?

When a motor maxes out at 100% but the error sticks around, Integral piles up a huge value. Once the error clears, that buildup sends it flying past the mark. We fix it by clamping the Integral limits.

Can I run just a P-controller, skipping I and D?

Sure, but you'll get 'steady-state error' almost every time. Like a P-only cruise control settling at 55mph when you want 60 – it can't fully beat wind drag. 'I' closes that final gap.

What's the usual loop speed for AGV motor control?

High-speed AGVs run it at 1 kHz to 20 kHz. Too slow, and it can't keep up with terrain shifts or sharp turns – cue instability or wipeouts.

How do I manually tune a PID controller?

Ziegler-Nichols is a go-to. Start with P only and crank it up till it oscillates. Add D to kill the wobble. Then a touch of I for any leftover offset – but easy does it to avoid chaos.

Does PID work for steering differential drive robots?

Yep, but typically with two PID loops. One handles straight-line speed, the other tweaks steering angle to fix heading slip.

What sets Cascaded PID apart from regular PID?

Cascaded stacks loops inside each other. For a robot arm joint, inner loop nails torque super-fast, middle does speed, outer hits position. Way better performance and stability than one loop.

Is PID suitable for non-linear systems?

PID's linear, so it chokes on super-nonlinear stuff like robot arms with shifting leverage. But for AGV wheels, it's the gold standard. For tricky motion, pair it with Feed-Forward.

How does sensor noise affect the D-term?

Derivative hates noise – it measures error slope, so glitchy sensor spikes fake huge changes and jitter the motors. Slap a low-pass filter on that sensor data if you're using D.